ENERGY

Can we do it?

The eternal tug of war between the ministry of transport and the ministry of the environment is legend. But if the Zeitenwende in energy policy is to succeed, it will be down to Volker Wissing and Steffi Lemke. How can an industrialized nation transform successfully? Only by pursuing an energy policy free of ideological blinders and willing to embrace whatever technology works best.

Text: Karl-Heinz Paqué

Illustrations: Andrea Ucini

ENERGY

Can we do it?

The eternal tug of war between the ministry of transport and the ministry of the environment is legend. But if the Zeitenwende in energy policy is to succeed, it will be down to Volker Wissing and Steffi Lemke. How can an industrialized nation transform successfully? Only by pursuing an energy policy free of ideological blinders and willing to embrace whatever technology works best.

Text: Karl-Heinz Paqué

Illustrations: Andrea Ucini

A breakthrough! That is what media outlets around the world called it when in December 2022 the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in San Francisco announced that, for the first time, it succeeded in fusing hydrogen atoms into helium releasing more energy in the process than was contained in the fuel. After decades of research this is tremendous progress in nuclear fusion technology bringing it back as a contender in the race for the energies of the future. And we are talking about clean energy here because there is no greenhouse gas emissions and, unlike with nuclear fission, no radioactive waste either. Of course, there is still a long way to go until this technology reaches some kind of widespread adoption, both from a technical and from an economic standpoint. It could be decades before fusion energy will be a realistic option. But the door has been opened for a host of start-ups to transform this fundamental innovation into an economically viable and standardised technology – just like the big developments and inventions in engine technology, electricity and microelectronics.

What are the consequences of the political end to nuclear power?

All of a sudden irreversible preliminary decisions on the expansion of renewable energies have a question mark behind it. Wouldn't it be better to remain open to a peaceful usage of nuclear energy after all, instead of insisting it has no future, all the while fixating on the past? Isn't it possible that all those other countries that decided to keep nuclear power as a small addition to their energy portfolio and continue to do research in that field might be right? Isn't Germany making a big mistake with dire technological and economic consequences if it goes through with is plan to shut down all nuclear power plants in April 2023 instead of keeping at least a few of them operational and waiting to see what happens? The fact is, green ideology has been setting the tone in Germany's energy policy for a good two decades now, preventing an unbiased assessment of nuclear energy for dogmatic reasons. That is as grotesque as it is dangerous: the founding myth of a single political party is dominating the future of energy policy for more than 80 million Germans and thwarting many European plans that could potentially be in conflict with it.

And of course nuclear energy is just one example – albeit an important one – of the catastrophic track record of fundamental decisions in energy policy taken in the Merkel era; all of which were promoted or even forced for partisan reasons by the way. Top of the list is of course the dependency on Russian gas which is now being ended for irrefutable geopolitical reasons – most likely for a very long time to come unless Putin is overthrown and there is a process of democratisation in Russia. Politicians in Central and Eastern Europe did warn Germany about this horror scenario repeatedly during the Merkel era. Alas, nobody wanted to listen.

Delays in building the necessary energy infrastructure, e.g. LNG terminals, have dire consequences today.

Planning takes far too long

Another hugely detrimental factor is a multitude of delays in building the necessary energy infrastructure: no LNG terminals and not enough wind turbines were built, progress building solar power systems was slow and the expansion of the grid for energy transport was sluggish, too. On top of that, a lack of digitalisation prevented a smart control of energy consumption and an efficient exploitation of savings potentials. All of this had to with a huge underlying problem: Getting a large infrastructure project approved takes way too long in Germany, no matter what kind of infrastructure is concerned. A comparison with European neighbours makes this all too clear; consider for example how quickly railroads are built in Switzerland or France and how swiftly construction on the Fehmarnbelt tunnel under the Baltic Sea was greenlighted in Denmark.

In Germany, there is a strange discrepancy between downright cocky announcements (“by 20xx there will be ...”) and the deplorable conditions in reality. They decide to usher in the era of electric cars by the 2030s (only one decade away!), but they are stalling when it comes to building roads and bridges, even though, clearly, electric cars need paved roads, too. They want a massive shift of freight from road to rail but are still accepting a hopelessly overstretched rail network that is not being expanded and modernised fast enough; some of the signal boxes are a hundred years old. It is a policy of illusions shaped more by German idealism than by German engineering prowess.

Even though Germany can act pretty damn fast when the political will is there. After German reunification, the economic reconstruction of East Germany known as “Aufbau Ost” was celebrated abroad (much more so than at home) as an impressive accomplishment and a testament to the country's extremely well organised industrial power. Everything went much faster than usual back then; and also faster than in the neighbouring post-socialist countries to the east, by the way. In recent months there have been encouraging signs, too. That the first LNG terminal on Germany's North Sea coast was finished in time came as a surprise to many. Seems like we ourselves didn't really believe in German efficiency any more, a quality that has historically been praised so much in other countries.

Planning takes far too long

Another hugely detrimental factor is a multitude of delays in building the necessary energy infrastructure: no LNG terminals and not enough wind turbines were built, progress building solar power systems was slow and the expansion of the grid for energy transport was sluggish, too. On top of that, a lack of digitalisation prevented a smart control of energy consumption and an efficient exploitation of savings potentials. All of this had to with a huge underlying problem: Getting a large infrastructure project approved takes way too long in Germany, no matter what kind of infrastructure is concerned. A comparison with European neighbours makes this all too clear; consider for example how quickly railroads are built in Switzerland or France and how swiftly construction on the Fehmarnbelt tunnel under the Baltic Sea was greenlighted in Denmark.

In Germany, there is a strange discrepancy between downright cocky announcements (“by 20xx there will be ...”) and the deplorable conditions in reality. They decide to usher in the era of electric cars by the 2030s (only one decade away!), but they are stalling when it comes to building roads and bridges, even though, clearly, electric cars need paved roads, too. They want a massive shift of freight from road to rail but are still accepting a hopelessly overstretched rail network that is not being expanded and modernised fast enough; some of the signal boxes are a hundred years old. It is a policy of illusions shaped more by German idealism than by German engineering prowess.

Even though Germany can act pretty damn fast when the political will is there. After German reunification, the economic reconstruction of East Germany known as “Aufbau Ost” was celebrated abroad (much more so than at home) as an impressive accomplishment and a testament to the country's extremely well organised industrial power. Everything went much faster than usual back then; and also faster than in the neighbouring post-socialist countries to the east, by the way. In recent months there have been encouraging signs, too. That the first LNG terminal on Germany's North Sea coast was finished in time came as a surprise to many. Seems like we ourselves didn't really believe in German efficiency any more, a quality that has historically been praised so much in other countries.

Fewer dependencies

Even more impressive is Germany's tour de force to wean itself off Russian fossil fuels. Before the Ukraine war Russian natural gas accounted for 55 percent of Germany's total gas consumption. A mere ten months later that percentage has dropped to zero. Same with coal, where imports from Russia were reduced from 50 percent to zero, and with oil, where imports were brought down from 35 percent to a little over 10 percent. And all of this without a collapse of the German economy or the energy supply to private households, mind you. There is one sentence that has been repeated by media outlets over and over in recent weeks and that is both literally correct and a symbol of Germany's latest success: gas storage facilities are full!

While the government did step in to help stabilise the situation quickly, launching enormous relief programmes and offering broad-based support packages (at considerable cost), it remains to be seen to what degree they will actually be drawn down. So far, evidence seems to suggest that businesses, especially manufacturing companies of the German Mittelstand, prefer to try and do everything they can to adjust to the situation before accepting help by the government, because they fear their reputation might take a hit.

The lesson in all this is: where there's a will there's a way; as long as you act decisively. What do we need to do? The hasty zeal displayed during the immediate response to the crisis must to be converted into a sustainable commitment to modernise our infrastructure. What we need is a new mindset – like back in the 1990s when Federal President Roman Herzog laid the mental groundwork for the required labour market reforms including Hartz IV by famously saying Germany needed a “jolt”. That is just what we need today, too.

Accelerated approval procedures for faster projects

It is true for all types of infrastructure. A key element must certainly be accelerated administrative processes: projects need to be executed faster. The so-called traffic light coalition did commit to this in its coalition agreement which stipulates that the duration of approval procedures shall be cut by half by making the necessary adjustments to the legal framework. This has an impact on all projects, including but certainly not limited to environmental and climate protection projects, as digital and transport minister Volker Wissing (FDP) has been right to point out time and time again in his dispute with environment minister Steffi Lemke (Green party). Politicians need to understand that the urgently needed modernisation of the infrastructure is a holistic challenge. You cannot distinguish between “good” and “bad” areas there, because it is all connected. The jolt that is needed in Germany pertains to the situation of the country as a whole, not only to an ideologically motivated selection of individual areas.

Making Germany fit for the future again can only be successful with a broad-based initiative. We are talking about nothing less than the transformation of a pre-eminent but visibly aged industrialised country to take it from the world of the 20th century into the world of the 21st century – and doing it in a geopolitical environment that has changed rather abruptly this year. It is a daunting challenge. We will have to prove in the next few years that we are up to it.

There is a lot to do

There is a lot to do

Climate neutrality, innovation and a modern infrastructure do not only require money, they also need to be planned and approved in an efficient manner. The traffic light coalition has set out to cut the duration of administrative procedures at government authorities by at least half. If they are successful, the transformation of the economy can pick up speed, our climate will be better protected and the economy will grow.

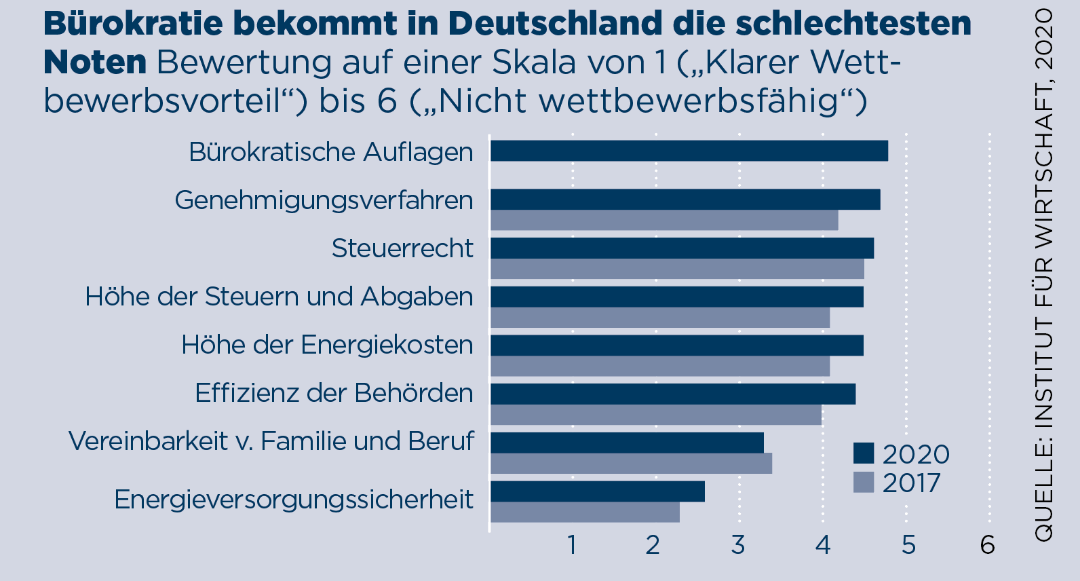

Bureaucracy is rated worst

Assessment on a scale from 1 (“clear competitive advantage”) to 6 (“not competitive”)

Climate neutrality, innovation and a modern infrastructure do not only require money, they also need to be planned and approved in an efficient manner. The traffic light coalition has set out to cut the duration of administrative procedures at government authorities by at least half. If they are successful, the transformation of the economy can pick up speed, our climate will be better protected and the economy will grow.

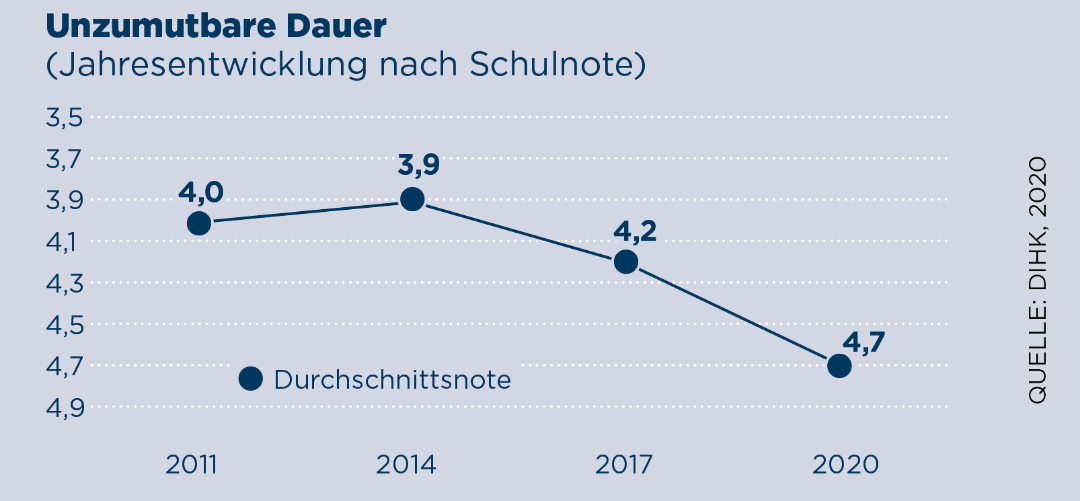

Unacceptable timeframe

(Yearly development based on German school grades from 1 (very good) to 6 (fail))

Red tape as well as drawn-out planning and approval procedures are paralysing Germany. That is why cutting down on bureaucracy is high on the list of urgently needed improvements, especially for manufacturing companies of the German Mittelstand, according to surveys done by the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK) on a regular basis. “Number and clarity of bureaucratic requirements” as well as “duration and complexity of planning and approval procedures” are at the bottom of the list of locational factors.

Karl-Heinz Paqué is Chairman of the Board at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. He is an economist and holds the Chair of International Economics at Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg. Global economic development is a subject he has been interested in since he was a university student in the 1970s. Ten years ago he already published a book about the consequences of demographic change: “Vollbeschäftigt, das neue deutsche Jobwunder” (full employment, Germany's new job miracle).

Karl-Heinz Paqué is Chairman of the Board at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. He is an economist and holds the Chair of International Economics at Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg. Global economic development is a subject he has been interested in since he was a university student in the 1970s. Ten years ago he already published a book about the consequences of demographic change: “Vollbeschäftigt, das neue deutsche Jobwunder” (full employment, Germany's new job miracle).

Also interesting

Anders Mertzlufft und Eva Cheung // „Ich will doch nicht den alten Laden der Männer aufräumen“

Veraltete Strukturen gehören aufgebrochen, darin sind sich Maren Jasper-Winter und Catharina Bruns einig. In einer modernen Arbeitswelt kann Frau gleichberechtigt sein – mit den richtigen wirtschaftlichen und politischen Anreizen. Ein Streitgespräch.

Karl-Heinz Paqué // Würdigung der Vernunft

Horst Möller durchwandert die deutsche Geschichte der letzten 100 Jahre.

Christoph Giesa // Meinungsvielfalt in Post-Ost

Die russlanddeutsche Community ist viel bunter, als man glaubt, sagt Irina Peter. Sie ist Co-Host des Podcasts „Steppenkinder“ und so etwas wie die Stimme der Aussiedler-Community in Deutschland.